All About AI: Bridging Human and Machine – Practical Implementation for an AI-Enhanced Future

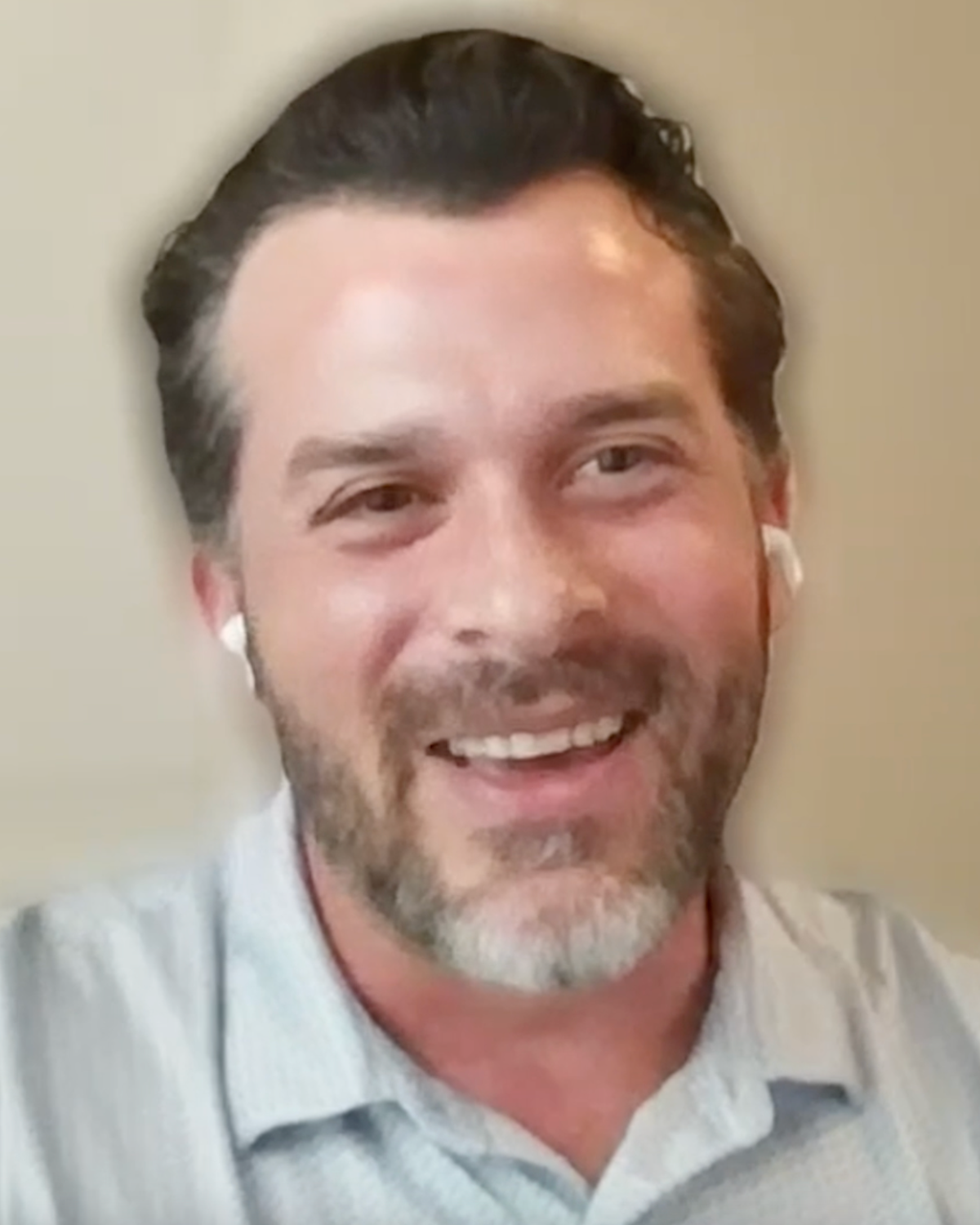

Hosted by Aaron Burnett with Special Guest Boaz Ashkenazy

Boaz Ashkenazy, CEO and co-founder of Augmented AI, joins us this week for our “All About AI” series to explore the delicate balance between AI integration and human capabilities in modern organizations. Boaz shares his extensive experience leading augmented reality and AI teams to demonstrate how businesses can effectively implement AI while preserving and enhancing the human element. Through practical examples and real-world insights, Boaz offers a measured perspective on AI’s current capabilities, limitations, and the pragmatic steps organizations can take to thrive in an AI-enhanced future.

About Boaz Ashkenazy

Boaz Ashkenazy is the CEO and co-founder of Augmented AI, where he helps businesses grow through the practical application of artificial intelligence. He’s also the host of Shift AI, a highly acclaimed podcast that explores how AI and machine learning are changing the way we work in the digital age.

Through his work and his interviews, Boaz has had the opportunity to speak with hundreds of thought leaders, inventors, physicians, and technologists in the realm of AI. Boaz founded his first augmented reality company in 2006 and has since led augmented reality and AI teams for Meta and founded and sold a virtual meeting platform company.

Listen & Subscribe:

Professional Background and Journey

Aaron: So tell me about Augmented AI and, in particular, tell me about your career trajectory and how that prepared you, I think fairly perfectly, for this moment and what you’re doing now.

Boaz: I’m from Los Angeles originally, and I moved to Seattle after living in San Francisco for a long time to study at the University of Washington. I got my master’s in architecture with a focus on computing and computers. At the time that I graduated and started practicing architecture in Seattle, it was a big transition in the commercial real estate and architecture space towards computing.

After practicing for a little while, I had the opportunity to start a software company focused on architecture and real estate. We got really deep into that vertical and understanding visualization and software related to that space. What was interesting about that at the time was that a couple of companies were coming up.

One of them was Oculus. This was before Facebook bought them. And then there was a secret program at Microsoft that was the HoloLens project, which is no longer in existence in the same way that it was back then. We got involved in the first HoloLens Academy as a company and started to do some interesting things.

From there, I started a couple of other companies, one in the e-commerce space, another one that was related to 3D experiential Zoom-like remote meetings. It was a really interesting time. Then Facebook approached me and asked if I wanted to join the company.

The reason why I said yes was the team was really interesting. It was on the enterprise engineering side of the organization. It was a small team at the time—we ended up growing really fast—but we built applications for employees. It was very internally focused. We touched a lot of different teams within the company, everybody from facilities and data centers to security guards, engineers, and recruiting.

At the time that I got hired, everybody was sent home, so we were building a lot of collaboration tools. There was some machine learning and AI chatbot work happening at the time too, but this was before the name change. A lot of the focus was on the headsets that were getting built, and that team ended up shipping almost 30,000 headsets to employees.

We ended up building and helping build a bunch of applications for internal use. It was that experience that really got me excited about the ways that internal operations inside of a company could work. One of the engineers on that team who specialized in machine learning, when ChatGPT came out, got really excited about gen AI.

He wanted to leave and start a company, and we were joined by another entrepreneur from Seattle. His name is Larry Arnstein, who is a really amazing entrepreneur and technologist. He was a professor at the University of Washington and spun out a bunch of companies very early in AI. One of the companies was called XNOR.AI, another one was called Impinj, which ended up going public. We were just really lucky to get two amazing entrepreneurs, Ashwin Kadaru from Meta and Larry, and started a company focused on helping businesses become AI-ready, navigate this AI journey that everybody is on right now, and promote really good data governance in preparation for what it takes to be able to take advantage of all these amazing new tools.

Aaron: Yeah, I think what’s fascinating and compelling about your background among many things is that you’ve been focused on virtual reality, augmented reality, and sort of the intersection with machine learning for a much longer time than is true of most people. Since the advent of, since the public release of ChatGPT, there are all sorts of people who’ve spun up companies and declared themselves to be expert consultants, but you’ve been in this space since I think 2006.

Boaz: Yeah, 2005 is when we started the first company.

Current Work and AI Implementation

Aaron: Tell me more specifically about the work that you do with Augmented AI. What kinds of engagements do you take on? What’s the process look like? And give me a sense of the outcomes that you achieve as well.

Boaz: Yeah, it’s really true in these hype cycles. There are a lot of folks that get involved and become “quote-unquote experts,” and I really rely on my two co-founders and partners who are the technical side of the business. What’s interesting about what they’re doing right now is they’re really rolling up their sleeves and going deep into the code and trying to understand the limits of large language models.

When we look at the work that we’re doing, we bucket it into a couple different categories, but I would say that across all those categories—I’ll explain more—but across all those categories, we’re doing the same thing, which is looking at where a lot of the unstructured data is inside a business, which typically is where a lot of the manual work is happening, and figuring out ways of getting that into structured format.

Inside a digital backbone, whatever those businesses happen to have. And I think that’s what, in a lot of ways, what these large language models are really good at. Most people think about AI, they think about ChatGPT, and that’s the obvious piece. When you look at use cases like customer service or search, a lot of that—the interface that you experience—is a chat interface and that’s obvious, but large language models can do all sorts of things that are invisible behind the scenes that really are amazing for internal workflows.

And so what we do is we look at where those opportunities are. To answer your question about what we do for businesses, that’s a big part of it. Businesses come to us, especially now with boards—sometimes it’s boards saying, “Hey, what’s your AI strategy?” CEOs asking CTOs what their AI strategy is. And a lot of people know they have to do something. They just don’t know what to do.

And they also don’t know where the ROI is exactly. And so we’ll do an opportunity assessment where we go in. It’s like business therapy—we go in and we say, “Tell us about your problems, what are your challenges?” In the back of our minds, we’re looking for those places where a lot of manual work is getting done and we’re trying to be honest about what is feasible with gen AI, what is conventional software, where is conventional software necessary inside the business.

And it’s not always the magic AI that is going to be applied. And even if it is, sometimes the ROI doesn’t make sense, and so we try to be honest about that. And then if we can see nuggets of opportunity, then we will do validation of those opportunities. We call it concept validation, but what we’re doing is really standing up instances where we can test the inputs and validate the outputs, and only then do we take it into operations and operationalize it.

Some examples of some of the things that are interesting—one of them is data ingestion. We call it universal import, but there’s a ton of businesses that are bringing in a lot of documents into their businesses, really complicated. And when you look at a lot of the advertising around AI, they say “Take your PDF and put it into ChatGPT and ask a bunch of questions” and it’s like this magic. And in a lot of cases, that does work if the unstructured documents are pretty simple. But the minute it gets complex—like we have some financial services companies that are using payroll data and financial statements and things where if you looked at the PDF as an image, if a human looked at that PDF, they would understand much of it, but they have to pull out and parse the information and put it into a table or a form or a structured database.

Boaz: When you just take that PDF and have a computer look at it, just the text of it, it can often get confused, and that’s where the problems are. And so what we’re trying to do is say, “All right, maybe we can take the image of it and the text, and together different large language models look at that and make sense of it so that you can parse that information and get it to a very high accuracy level.”

The same thing is true for search. People are using large language models to ask questions in natural language in English against very large databases. And what’s happening behind the scenes is code is getting written—Python, SQL—and then it’s returning natural language. So from the user standpoint, it’s great because you can get much closer to the data. If you’re a revenue generator in a business that doesn’t know how to write code, you use English and then hit the database.

The problem is that sometimes, and you won’t be surprised by this, but if the data is not good, the large language model can easily get confused. It’s the classic garbage in, garbage out scenario. And so being able to clean that up, but also structure elements of it to help the large language model along, is a big part of the job. When I look at what a lot of the technical people are doing in our business, a lot of it is understanding where the limits of the large language models are and helping it to be awesome because it is incredible technology for sure. It just needs a little help.

Aaron: And I think incredible technology when it’s employed in a manner that’s governed by the practical reality of what it’s good at and what it’s not good at. I would imagine that in many instances, it’s a relief to a technical leader in a company to know that AI is not magic for everything—to hear that it has limited and specific utility. There are other areas where more conventional software applications are going to continue to reign supreme.

Boaz: Absolutely, especially in this environment. Because we’ve gone through these phases of different hype cycles in the last 10 years, and I think technologists are wary that they will go down a path and then have to crawl back. And the other thing, too, that I think they—and I think that’s the thing that we should appreciate—is helping them tell stories about how this relates to business value and when it doesn’t. And we try to do that a lot too.

Aaron: I have had periods where I’ve looked at particularly the publicity around AI or use cases that are claimed, particularly by futurists, and it can be disorienting. I can think, “Have I completely misunderstood how this works, things will work in the future, and how they work today?”

So even for me, it is reassuring to know, “Oh no, this—you can understand where this technology should and should not be applied.” And there is a rational process associated with that.

Boaz: Yeah, definitely.

Aaron: Can you give a couple of examples of outcomes that you’ve been able to achieve or particularly novel use cases?

Boaz: One example is this financial services example where a lot of human work was being done by a team to be able to parse a lot of this data coming into the business, and by deploying this technology, hours and hours can be saved. However, there still is an interface where humans are in the loop—experts are in the loop being able to make sure that last mile is being checked and that things are going out the door and they’re accurate.

And in that particular case, I think that it’s time that’s being saved—a lot of time that’s being saved. We’re also working on knowledge bases for businesses where internal knowledge is protected from the general knowledge that’s being trained on those models so that you can have really accurate information about your business.

Aaron: Yeah.

Boaz: And that technology is pretty common. It’s called RAG technology, but we’re doing it in a very specific way to increase the accuracy of the answers that are coming out of the model. I can get into more technical detail on that, but what’s great about that is that through this process, you can get answers. You can ask questions about our business, you can get answers, but it can also ask you questions in return. And we’re doing this for different kinds of businesses. We’re doing it for a tax advisor, we’re doing it for another financial services company. And I think it’s that kind of back and forth conversation that I think a lot of people are gonna start getting used to when they hit chatbots for different kinds of businesses and for different kinds of use cases.

Aaron: Yeah. Anyone who’s paying attention to AI is familiar with the notion of hallucination and the often offered caution around AI that you can’t trust the information you get back. But assume that in the instances in which you’re working, accuracy is paramount, particularly in a financial services company and those sorts of things. How are you able to ensure much greater accuracy, acknowledging that perfection can’t be achieved with people?

Boaz: All right. I’m going to give some tips out there to folks that are trying to figure this out and are having problems getting accuracy from these models. In a lot of cases, we are not letting the models use the training data, the general data for answers. These language models are really great at language—amazing. They’re amazing at all different kinds of language, code and translating languages and English and so on. They can struggle with facts unless you really force them on certain data sets.

And that’s one of the things we do. We also tell those models: don’t answer with conviction if you don’t know the answer. And if you don’t know the answer, say you don’t know the answer. And maybe it means that we need to move you to a human in the business that can answer your question on the phone.

So we try to really push the answers to be honest. And then the last thing that we found is—and this is getting a little more technical—but it’s interesting because when you use a RAG method for a chatbot, what you’re doing is you’re taking a bunch of content and you’re chunking it up in little pieces, and you’re putting it into a vector database, which is an AI database.

And oftentimes, even though those chunks of data have adjacencies to them, they’re based on meaning, they can get confused about the data. And so one of the things that we’ve realized is that questions and answer databases are much easier for the large language models to understand.

So if you ask a question, and inside the database is a vector for question and a vector for an answer, it becomes much more accurate. The return of the answer is much more accurate. And so we’ve been using large language models to take large amounts of data, turn them into Q&A databases, and then ask the question against the Q&A database.

And that’s been a trick that we’ve been using that’s been really accurate. We’ve been doing it for text, also been doing it for images. Images and descriptions work the same way in these vector databases, and it makes the returning result very accurate.

Misconceptions About AI and The Future of Work

Aaron: What do you think is misunderstood about AI?

Boaz: I think that one of the things that’s misunderstood is the limitations and how powerful it is right now. I think that a lot of lay people just think it’s magic and think it’s going to be able to do everything inside of a business and, as a result, take their jobs. When you talk to people on the street that don’t know a lot about the technology, there’s a lot of fear—the fear of the robots taking over the world, the fear of losing their jobs.

And I think there are a lot of jobs that are going to get lost. I’m not trying to pretend that’s not true. I think there’s a lot of jobs that are going to get created too—very different jobs. And I think there’s a little misconception about how fast that’s going to happen. We’re still very early. Even though in the media, it feels like the robots are going to take over the world.

Aaron: Let’s explore this a little bit further. You said there are certain types of jobs that will be lost, others that will be created. What is your rubric or framework for identifying or considering those jobs that are likely to go away and those jobs that are likely to be created?

Boaz: I can tell you that an example of a job that’s going to be created is one that’s related back to that knowledge management example that I gave you. I think there’s going to be a lot of jobs related to the curation of data inside businesses, the cleaning up of data inside businesses, and the preparation of that data.

There’s going to be dedicated people, just like there were before—before the internet created these web developers. And I think knowledge managers is a new job, and it’s going to be a new job in a lot of businesses. I also think that the concept of expert in the loop in a law firm, for example—some of the senior folks in that firm are not going to go away, but some of the junior people are.

And that’s going to be a trick for a lot of businesses too, is like how with the power of these tools to do a lot of the work that interns were doing, how are we going to train the next generation to become the senior-level folks in the organization?

Aaron: Yeah.

Boaz: And I think that’s a big challenge. I don’t have an answer for that, but I think it’s gonna be a big challenge.

Aaron: I’ve been wondering the same.

Boaz: Yeah.

Aaron: The implications for digital marketing are very much the same. Anything that can be that is repeatable, that can be documented, that is a consistent process now or in the not-too-distant future can be either completely replaced with AI or can be significantly supported by AI. So that now you need just fractional attention from a person, but you become expert through time and repetition. And if you don’t need junior employees to get that time and repetition, I’m not sure how experts are cultivated.

Boaz: It points me to a question that I get asked a lot too. It’s like, how should I prepare for a future that looks like that? What if I’m a student, what if I’m younger? Like, how should I think about that?

Aaron: Yeah.

Boaz: I don’t have a great answer, but one thing I have been trying to tell people is that specialization is way more important than it ever was. And going deep on a particular vertical as an individual, also as a business, is going to separate you in a way, in a world where these models at a very general level can answer so many questions and do so many things for us. I think there’s still going to be a part of specialization on whatever topic that you happen to be interested in that is going to separate you from the pack.

Aaron: I do wonder, and as you said, I don’t have an answer for this. I do wonder whether the specialization should be deep and vertical or should be broad and horizontal because I think that sort of expertise that is unlikely to be displaced by AI is strategic orchestration.

Boaz: Give me an example in the marketing world. How does that show up for you?

Aaron: Historically in the marketing world, you might be a search strategist and have a very deep level of technical expertise regarding search engine optimization. I don’t think that has enduring value in the same way now that it did in the past. Instead, what we’re focused on cultivating is digital strategists who are broad marketers, who have an understanding of the strategic value and utility of all of the digital marketing channels and their place within the larger marketing organization or marketing strategy, who can orchestrate those channels and behave much more as a business and digital marketing consultant, rather than someone with very deep expertise in one particular area.

Boaz: Yeah. That’s interesting. I guess the conductor is the metaphor, the orchestra conductor, right?

Aaron: Yeah. And it is in our experience, it is increasingly true that we can generate much stronger returns when we have strategists employed, when we’re engaging as—we call it one wheelhouse. It’s a complete agency. It’s not just a search engagement. It’s not just an advertising engagement. We’re using data science as well and complex analytics and all sorts of things in an orchestrated fashion. But that requires a strategist who understands all of those disciplines well enough to orchestrate them and understand how they complement one another.

Boaz: What if it’s a broad understanding of disciplines, but a very tuned vertical?

Aaron: That has real value. And that actually, that notion has been around for a long time. The notion of a T-shaped marketer—understand all of these things, I go deep on one or two—that has value, but I think deep on one or two without the broader understanding creates risk.

Preparing The Next Generation

Aaron: We both have kids. We were talking about this a little bit as we got started. What are you talking with your kids about? What are you telling your kids about how to prepare themselves? How to envision a career or a job that may or may not exist today?

Boaz: I think it’s an exciting time to be young and thinking about this space. I think there’s a lot of apprehension with my kids about the technology, but there’s a lot of excitement too—both sides. And the thing that’s exciting is that the amount of free information that’s available to people right now is just astounding, especially with AI, both for people that want to learn how to code and people that don’t want to be so technical.

It’s just anybody with a little bit of motivation can find these resources and take advantage of them in a way that was just not available to me. And also we’re early. It may not feel that way because it’s a hype cycle and everyone’s got AI in their minds. We are very early. And so if you’re a young person that’s interested in a particular field, and you want to understand AI in that field and learn a lot about it, you’re going to be well positioned.

There’s a lot of opportunity for my kids, for example, to take advantage of that. I have one child that’s a musician, another child that’s a writer, and it’s very different, but I think that for the musician, even though there are a lot of tools that are getting created to be able to write music, I think it’s interesting to think about the opportunity to be creative and take advantage of these tools at the same time, and understand how to play around with those two different dualities.

Aaron: Yeah.

Boaz: And the same thing is true for writing. Obviously these large language models can write pretty well, but where are the things that are human about both creation of music and creation of writing that can couple together with the power of AI, turn those into things that are even better? And I truly believe that humans plus machines are more powerful than machines by themselves. I know there’s a lot of folks in Silicon Valley that disagree with me, but I’m optimistic about the idea that the things that are really powerful about us as humans, coupled with AI, can be even more powerful than these agents that we’re hearing about.

The Changing Nature of Work

Aaron: I strongly suspect that the hand wringing you alluded to in Silicon Valley is a core part of a very shrewd PR strategy. It’s a way to get a lot of attention. I think there’s something that I’ve been thinking about and wrestling with—I think there’s a fairly profound implication for what is considered the nature of work. Historically, work value was time plus effort. There had to be labor involved. It had to feel like work.

Aaron: And there is that sense of feeling like work that, when you’re using AI for the right application, goes away. There are things that I’ve done that were too easy. The outcome was better than I would have achieved on my own with more time. But I felt very conflicted at the fact that I did something in 15 minutes that might’ve taken me a couple of days before.

And at an almost ethical level, I felt uncomfortable with how easy it was to achieve that outcome. Where as an agency, we’re quite conservative. We don’t use AI for client deliverables. We’re not at a place where we feel like we’re confident enough in the value delivery and the consistency of the value delivery for things like content or strategic documentation and that sort of thing. But we use it for internal work. Do you share that sense of sometimes unease and how easy and frictionless work becomes and whether in fact that still feels like work? There’s something about doing work that I think is soulfully satisfying—applied effort and you achieved something. You don’t have to apply effort in the same way. I wonder about how that feels.

Boaz: Yeah. I definitely think that from the outside, when people hear that people are using AI for their work, there’s this feeling like, “Oh that’s cheating.” I think also that internally, like I talked to some young people, students who are being quiet about how they’re using this. And oftentimes they’re bringing their own AI to the office but not telling anybody. Or they are doing this work, it looks like they’re being very productive, and because of the competition inside the organization, they don’t want to share what they’re doing with others. And so I think there is some tension and there’s some unease about this.

I still think that there’s a lot of people that are not just letting the content go out the door. They’re touching that content. They’re making decisions about whether to use this or not that. But the prototyping of ideas and creativity can happen really fast. And so I take it that internally you may be using it for some of those things—”Hey, I’ve got some ideas about X, Y, and Z. I need you to give me seven or eight things that I should be thinking about. What am I missing?” And then from there, with your experience, you’re taking that and doing what you need to do with it.

Aaron: Yeah.

Boaz: My fear is that over time, society is going to lose its edge when it comes to creation of whatever it happens to be that they do. In your case, let’s say it’s marketing copy, and somebody else’s case, it’s research related to some sort of topic. It’s the DocuSign phenomenon, which is “I don’t read the contract, I just click click.” I’m worried that’s going to happen for a lot of different—I’m already starting to see that happen for a lot of things.

I’ve heard some recent stuff around using large language models to create police reports. And there was just some—it was great. And in often cases, they were better written police reports than typically were written, but in some cases they were missing things. And there were all sorts of other legal implications that made it not something that people wanted to use. People were getting so comfortable with it. It was so good at summarizing that they weren’t reading everything.

Boaz: And I’ve heard of this with coders too, right? You know that they’re writing code, that it’s actually doing a great job of helping them along the way, but they’re not reviewing the code in the same way that they used to. And I just think that’s going to be a societal implication that we’re going to need to deal with.

Aaron: I think that has the potential to be corrosive with regard to expertise. So again, there’s a conundrum. What we need are people who are deeply expert, but the easier AI makes things, the less expertise people will have available to them.

Boaz: It’s an educational thing. In my mind, I think we’re gonna have to teach people a different way of experiencing the information that they’re learning and the way that they’re writing. It’s much more managerial and much less individual contributor. I’m going to sit down and I’m going to write this article.

Aaron: Yeah.

Boaz: There’s much more editing involved and it’s still very creative. It’s just a different kind.

Insights From The Shift AI Podcast

Aaron: Yeah. It’s the changing nature of work. So you also host a fantastic podcast called Shift AI. This one, I think you’ve hosted just under 50 episodes and you’ve spoken with a broad swath, a diverse group of guests—everyone from ethicists to venture investors, entrepreneurs, CEOs, folks in large organizations. What have you heard that has surprised you?

Boaz: It’s interesting. I started that podcast when I was at Meta, and it was really focused on the future of work. When I started, I interviewed a lot of Meta folks, interviewed vendors that we were working with. And when I left to start Augmented AI, it was syndicated by GeekWire and I started interviewing people from a much broader range of positions—politicians thinking about policy, founders and investors for sure, incumbents, mostly Amazon, Microsoft, but other incumbents as well, and folks in the educational space too.

And so that’s been really—it’s been really cool to see a lot of different perspectives around this. And recently there was an episode on education that really hit me, and it was a woman who had spent her career studying Montessori schools and looking at the way that those students learn and then thinking about what the implications would be like in a future where AI was going to dominate both higher education and K through 12. It really struck me how she was thinking about the human part of learning and how that was going to show up for us in the future.

Boaz: And it got me thinking about what as humans are we good at and what value are we going to bring in a future where a lot of these tasks are just going to get done by a machine? And that’s one of the things that, you know, whether it’s the emotional side of us or our ability to deal and coach teams and manage people and have intuition and be creative in very special ways. I just think that’s going to be more and more important as we are up against this technology that can do a lot of the stuff that we thought was part of our jobs. And that really hit me and it got me thinking like, what are the things that we do really well?

Aaron: I listened to that episode this morning and I do think she has a novel approach, novel way of thinking about things. In particular, in maybe cultivating a future in which AI is attuned not only to the intellectual or academic prowess of a student, but also their emotional state, physical state, and other things that also should be addressed as part of just cultivating healthy and rich learning. It’s a fascinating way to think about things.

Boaz: And it can be applied to someone really technical too. If you’ve spent the last 10 years writing code, and now 40 percent of your time is saved by tools that are writing the code for you, how do you fit in an organization, as somebody that just put their head down all day and wrote code, didn’t really want to talk to people, versus others who are cultivating a more managerial approach to building out teams and fostering teams and connecting with people, right? I just think that, perhaps the value proposition for employees is going to change.

Aaron: Yeah, I think there are clearly things that have happened societally over the last few years that work against those aspects of human nature where we should be cultivating expertise. As we all went remote, as we perhaps all became a little bit more introverted if we weren’t already, as we became less attuned to one another relationally, and we potentially atrophied those things that are at the core of the value that will be essential for us going forward.

Boaz: Yeah. Absolutely.

Aaron: The other episodes that came up for me were the political ones. Because we’re really in no man’s land right now in terms of policy. Talking to political leaders about what their constituencies are afraid of and what they’re excited about was really interesting.

Boaz: Joe Nguyen was a state senator from Washington who was on. We had another from California, Zach Friend was on the show. And we just had some really interesting legislation come out of Colorado and a veto of some big legislation in California. Europe is doing some things right now that are farther ahead from a regulation standpoint than the United States. And there’s been a lot of conversations about innovation versus regulation within AI that I think is going to play out in the next few years.

AI Regulation and Policy

Aaron: I suspect we talked about this as we were getting started as well, that Europe will lead the way from a regulatory perspective. They’ve done so with regard to data privacy as well with GDPR. Can you talk a little bit about what’s happening in Europe with regard to regulation of AI?

Boaz: Yeah, I think that so far they’ve passed the AI Act in Europe, and I think we’re going to see pretty tight regulation on how models can get built and how much transparency those models need to have, and also how much reporting. And there’s going to create a lot of friction, especially with the larger companies in terms of what they need to report. In a lot of cases, there are situations where large language models and assessment of individuals is going to be heavily regulated.

And we’re already starting to see that in the United States too, but in Europe they’re really coming down on that. And what it means is that if you’re going to use AI to score a resume and then eventually choose a person for a job, there needs to be transparency in why those scores are being allocated to those individuals. So the black box of just using large language models to come up with a number, I don’t think that’s going to be possible. I think you’re going to have to open the hood on what you’re doing. The same thing is true if you’re going to bring in applications and then choose winners for RFPs. You’re still gonna have the same kinds of transparency.

Future Outlook

Aaron: What will daily work look like five or ten years from now?

Boaz: I’m not sure all the jobs that are gonna get created in ten years. But I will say that the one thing I do know for sure is that AI is gonna be everywhere and it’s gonna be pretty invisible in a lot of ways.

Aaron: Yeah, I agree.

Boaz: Then in the way that it is right now, so many tasks that we do today are going to be done by a computer and we’re going to have to ask ourselves what our value is. And I think that intuition and emotional intelligence and the ability to coach people in a meaningful way, the ability to connect with others, build relationships—that’s going to be valued in a way that’s just not valued right now. We are going to be more creative because I think that part of our brain space is going to be freed up to be more strategic and more creative. I do believe that. And I think there’s going to be a lot of new jobs that I just don’t know of yet, that are going to need to be in existence in order for all this to work.

Notable AI Applications

Aaron: As you reflect on the very interesting guests you’ve had on the Shift AI podcast, what is one guest/company that has a particularly compelling application of AI that stands out for you?

Boaz: I interviewed a young founder based in Seattle. His name is Varun and the company is called Yoodli. It is a technology that listens to speeches—they could be recorded or they could be live—and it makes recommendations on how to be better at public speaking. And it does it in a really interesting way. Why I liked it is that technically, the idea that you could get a transcript of a speech and then summarize that speech or analyze that speech is not super novel technically, but being able to really impact people’s ability to speak in front of an audience and affect that and help people with that, because so many people struggle with that, is really powerful.

The other thing—it’s a different company, but I think the potential for translation to happen in healthcare could be really transformative. And I interviewed somebody that was talking about transcribing meetings between doctor and patient. And one of the things that there was a problem with was with very obscure languages. They had to have, on call, the right person to be able to translate, and oftentimes that wasn’t the case and it was—a lot of patients really struggled. And now there’s really an opportunity in real time to have any language that you want be translated. And I think that’s going to really impact the relationship between a lot of doctors and certain patients.

Aaron: I’m curious about Yoodli. Does it actually listen to the recording of a speech?

Boaz: It does. And the guidance that it provides pertains not just to word choice, but say, vocal inflection, speed of your speech. Are you saying ums, uhs? And I think it goes deeper than that as well in terms of are you getting the point across? What is the best way to get the point across? Are you trying to tell a story? Is the story landing?

Aaron: That’s very interesting. Very valuable. I know another company CEO that was trying to build something like that just for himself because he does a lot of public speaking.

Boaz: Yeah.

Aaron: So I know what to send him.

Boaz: That’s great.

Seattle’s AI Ecosystem

Aaron: What have we not talked about that we should?

Boaz: I’m also on the board of regents for the Seattle Chamber of Commerce and I’m the Seattle chapter president for an organization called the Applied AI Association. And in both those cases, I’m trying to give back a little bit and build a community that puts Seattle on the map. And so there’s been a lot of talk recently about why Seattle has fallen behind given the fact that we have two of the biggest cloud providers in the world and one of the best public universities in the world.

Why is the Bay Area and San Francisco still ahead? Why does Austin and Boston sometimes get talked about and not Seattle? And I’m also really interested and focused on how do we change that narrative? We have—there’s so much potential in this city and so many talented people. And so I’ve been working to try to figure out what is it going to take to change that? And I’m looking for other people that are interested in that topic too, to get involved and help.

Aaron: That’s a great mission. Are you connected to Chris DeVore?

Boaz: I know Chris, yeah. That’s a passion for him as well. Yeah. No, there’s a lot of people in this area that I think have that passion. Aviel Ginzberg just started a really interesting group of folks that are in Capitol Hill called Foundations. He was on the show talking about what he’s doing, and I think he’s trying to fill a really interesting gap. AI2 Incubator‘s Managing Director, Yifan Zhang, was also somebody that was on the Shift AI podcast, and they’re setting up AI House, which is a place to be able to have folks come and gather and talk about these issues.

So I think there’s a ton of potential. Our mayor is very technically focused and speaks to a lot of other mayors in a lot of other cities. And so yeah, I think we’ve got all the ingredients. We just need to put it together.

Aaron: Yeah. Yeah.

Boaz: I agree.

Aaron: I’m optimistic.

Boaz: Yeah.

Aaron: I really enjoyed talking with you.

Boaz: Yeah. Thank you. Thanks very much. Yeah, really had a great time talking with you as well.

Aaron: Yeah, me too.